Exploring Julia with SimPEG

I have been meaning to checkout Julia for a while, an open source (and real) alternative to Matlab for doing scientific computing. I left Matlab for Python a few years ago, and have not looked back. However, Julia touts a mash-up of flexibility and high performance, through a dynamic type system and a JIT compiler, which makes it hard to ignore. Julia is also taking aim at parallel computing and cloud networks, I am extremely interested in these topics both from a research and an industry perspective. My plan is to bring some of the functionality of the SimPEG meshing and optimization packages over to Julia to explore this new language in a goal oriented and useful way. I am also hoping that by documenting some of the differences between Python and Julia as I move code over, it may be helpful to someone somewhere.

The plan:¶

Partial differential equations using finite volume, we will be working on a TensorMesh in 1D, 2D and 3D, and want gridding, plotting, operators, averaging and interpolation. This is a big step on the way towards usable geophysical simulations, and will hopefully stress test my learning of Julia.

First off, let us look to the SimPEG code base in Python to guide what we want to do. There is a Mesh class in SimPEG that holds all information about the mesh structure, linear operators, and has methods for easy plotting. This uses object oriented programming (OOP), inheritance, and lazy-loading of properties. What I love about this is that the methods are attached to the mesh, so in IPython you can create a mesh, and dot-tab to see the properties and methods which are available to that instance. In Julia, there is no OOP, they have opted to use Types and Multiple Dispatch instead. This has a lot of advantages for parallel computing, but could be a bit harder to get started with a new library. Here we will look at the high level differences of the two packages.

In Python:

from SimPEG import *

hx, hy = np.ones(5), np.ones(10)

M = Mesh.TensorMesh((hx, hy))

Div = M.faceDiv # M has a property faceDiv which is loaded on demandIn Julia:

using SimPEG

hx, hy = ones(5), ones(10)

M = TensorMesh((hx, hy))

Div = faceDiv(M) # faceDiv is a function which takes a mesh (loads from M on demand)In Python, faceDiv is actually a @property which points to _faceDiv or creates it if it does not exist. In Julia, because we are dealing with Types not classes, we cannot attach fancy methods to the types, so what I have done is create a DifferentialOperators type, which is by default empty:

type DifferentialOperators

faceDiv::SparseMatrixCSC

# more operators here

endAnd then when we call faceDiv, we can check if the operators are defined and return them, otherwise we do some logic and store it in the Mesh.ops field:

function faceDiv(M)

if isdefined(M.ops, :faceDiv)

return M.ops.faceDiv

end

# logic to create D

M.ops.faceDiv = D

return M.ops.faceDiv

endThe ideas are pretty similar, but the code lives in different places, and, in Julia, is not attached directly to the Mesh object. Amazingly, I have gotten this far without even talking about the Mesh object, so what does that look like in a non-OOP language? We shall start with a simple 1D tensor product mesh, and define a Type for the mesh:

type TensorMesh1D

hx::Vector{Float64}

x0::Vector{Float64}

end

M = TensorMesh1D(ones(5), [0,0])In addition to these basic parts of the 1D mesh, I talked previously about adding in the DifferentialOperators as a property of the Mesh which allows us to store operators rather than recompute them every time. I want to add that in without changing the structure of the caller:

type TensorMesh1D

hx::Vector{Float64}

x0::Vector{Float64}

TensorMesh1D(hx, x0) = new(hx, x0, DifferentialOperators())

ops::DifferentialOperators

endThis creates a new dispatch method for the TensorMesh1D that has the signature:

TensorMesh1D(::Array{Float64,1}, ::Array{Float64,1})Wonderful, so now we have a Mesh type that stores the spacing and the origin. In reality I have also added some mixin-types for counting up cells in the mesh (e.g. M.cnt.nC). We could now feed this to faceDiv, and it should do something! However, what happens when we have multiple types of meshes (e.g. CylMesh, TensorMesh3D)? Each mesh should have its own faceDiv function. One thing that is awesome in Python is multiple inheritance, a 1D TensorMesh is a Mesh, a TensorMesh, and it has operators, inner-products and plotting functions. Each of these things are classes in SimPEG and we can just pull them all together to create a new thing; it makes code-reuse very easy. What is interesting is that Types in Julia cannot even inherit from other Types. Instead, Julia has AbstractTypes to include some structure in the Type Tree. This could allow you to create a function that accepts a Number type without caring too much if it is an Int or a Float etc. This is super important for Julia’s multiple dispatch system, which loads many functions of the same name that are distinct based on their typed inputs. The canonical example of multiple dispatch is the + operator, which has many different dispatches depending on what is being added. This is done in object oriented languages like Python by overloading methods in a class (e.g. __add__), and then letting the classes figure out how to do things dynamically. In Julia the ideas of multiple inheritance are still being hotly debated and I am not sure how well it would play with their multiple dispatcher, as things could get somewhat ambiguous. So without multiple abstract inheritance of types, we have to make a choice:

abstract AbstractSimpegMesh

#: by the dimension

abstract AbstractMesh1D <: AbstractSimpegMesh

abstract AbstractMesh2D <: AbstractSimpegMesh

abstract AbstractMesh3D <: AbstractSimpegMesh

#: or by the *type* of the mesh, heh

abstract AbstractTensorMesh <: AbstractSimpegMeshWriting it out now, it seems pretty obvious which road to choose, but I wanted methods which acted on either the dimension or on the idea of what the mesh was. Plotting of 2D meshes might be pretty similar, but maybe the differential operators are grouped by TensorMesh, CylMesh, FiniteElementMesh. Unfortunately, we cannot have the best of both worlds at the moment. I chose AbstractTensorMesh and separated dimensions by putting that in the M.cnt.dim property:

type TensorMesh1D <: AbstractTensorMesh

# 1D stuff

end

type TensorMesh2D <: AbstractTensorMesh

# 2D stuff

end

type TensorMesh3D <: AbstractTensorMesh

# 3D stuff

end

function faceDiv(M::AbstractTensorMesh)

# logic

endThis allows us to create a faceDiv method that is specific to the TensorMesh classes, and then have an if-statement over the dimension of the mesh. The entire faceDiv function is below:

function faceDiv(M::AbstractTensorMesh)

if isdefined(M.ops, :faceDiv)

return M.ops.faceDiv

end

# The number of cell centers in each direction

n = M.cnt.vnC

# Compute faceDivergence operator on faces

if M.cnt.dim == 1

D = ddx(n[1])

elseif M.cnt.dim == 2

D1 = kron(speye(n[2]), ddx(n[1]))

D2 = kron(ddx(n[2]), speye(n[1]))

D = [D1 D2]

elseif M.cnt.dim == 3

D1 = kron3(speye(n[3]), speye(n[2]), ddx(n[1]))

D2 = kron3(speye(n[3]), ddx(n[2]), speye(n[1]))

D3 = kron3(ddx(n[3]), speye(n[2]), speye(n[1]))

D = [D1 D2 D3]

end

# Compute areas of cell faces & volumes

S = M.area

V = M.vol

M.ops.faceDiv = sdiag(1.0./V)*D*sdiag(S)

return M.ops.faceDiv

endIt is almost identical to the implementation in Python (just add one), with the notable ease of use of horizontal and vertical concatenation, which is so much easier in Julia. For example, when concatenating the edgeCurl in Python compared to Julia.

In Python:

C = sp.vstack((

sp.hstack((O1, -D32, D23)),

sp.hstack((D31, O2, -D13)),

sp.hstack((-D21, D12, O3))

), format="csr")In Julia:

C = [[ O1 -D32 D23],

[ D31 O2 -D13],

[-D21 D12 O3]]I found it pretty simple to port the core of the SimPEG meshing functionality over to Julia, and the obvious next step is to package it up and share it with the world.

Packaging¶

It was easy. Check out the Julia docs on how to do it, but basically it takes one or two lines of code from inside the Julia environment. I was impressed with how slick this was.

You can use this now if you would like (go to Julia Box):

Pkg.clone("https://github.com/rowanc1/SimPEG.jl.git")

using SimPEG

hx = ones(100)

M = TensorMesh(hx, hx)

Msig = getFaceInnerProduct(M)

D = faceDiv(M)

A = -D*Msig*D'

q = zeros(M.cnt.vnC...)

q[50,25] = -1.0

q[50,75] = +1.0

q = q[:]

@time phi = A\q;As a sort of side note, it did actually take a lot of messing around to get the structure of the modules and the file system hooked up, I ended up going with something like this (but I am not totally happy with it):

SimPEG.jl

-> src

-> SimPEG.jl # Creates the actual package

-> Mesh.jl # TensorMesh code, would be nice if this was its own module

-> MeshCount.jl # Counting things in the Mesh

-> MeshGrid.jl # Things for creating grids and vectors from the Mesh

-> LinearOperators.jl # Differential operators and averaging stuff

-> Utils.jl # Utils that I take with me to any new language

-> test

-> runtests.jl

-> .gitignore

-> .travis.yml # Travis emails me when I break things

-> LICENSE # MIT, obviously

-> README.md # Read me all the thingsThe SimPEG.jl file was the most difficult to play with, I ended up doing something like this:

module SimPEG

include("Utils.jl")

include("Mesh.jl")

include("MeshGrid.jl")

include("LinearOperators.jl")

endI think what it basically does is inject the actual file into whatever name-space you are in. This is interesting, because I do not need references to Utils in the following files, because they are executed from the SimPEG module (which has the Utils in it). Weird. Another thing that I found difficult to grasp was all the different ways to bring things into a name-space (using, import, importall, export). See the docs for more details; I stared at this page for a long time.

Plotting¶

We have done a fair bit of work in SimPEG getting plotting really easy to do. For the TensorMesh these methods are attached directly to the mesh (e.g. M.plotImage(phi)). In Julia, plotting can be done by passing things to Python using PyPlot, which uses matplotlib. So Julia is calling Python to execute things and then returning an image to inject into the notebook (for example). The next question I asked was, why not use all of that SimPEG code that we have?! That is pretty easy actually!:

using PyCall

export plotImage

function plotImage(M::SimPEG.AbstractTensorMesh, vec)

@pyimport SimPEG as pySimPEG

Mesh = PyObject(pySimPEG.Mesh.o)

h = M.cnt.dim == 3? (M.hx, M.hy, M.hz): M.cnt.dim == 2? (M.hx, M.hy) : (M.hx,)

pyM = pycall(PyObject(Mesh["TensorMesh"]), PyObject, h)

pycall(pyM["plotImage"], PyObject, vec)

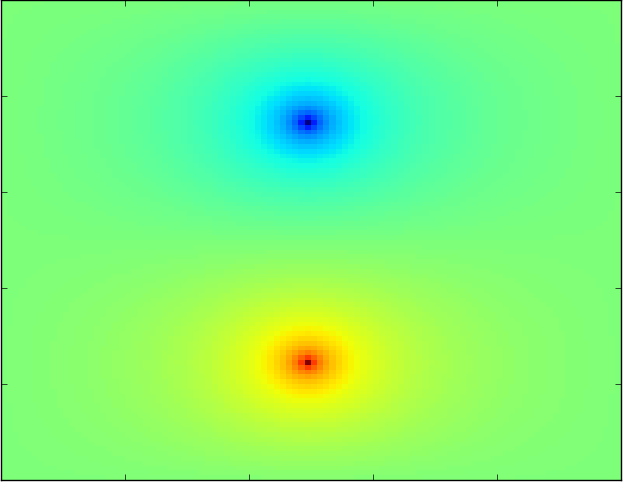

endThis code reproduces the SimPEG mesh in the python environment, and then uses it’s plotImage method for the vector. So now we can have Julia call Python to plot the image of the dipole that we solved above:

juliaplotImage(M, phi)

Plotting in Julia

It is certainly nice to bring the libraries functionality with you as we explore this new language! Interestingly, we can also go the other way (Python calling Julia):

import numpy as np

import julia

from julia.core import JuliaModuleLoader

j = julia.Julia()

S = JuliaModuleLoader(j).load_module('SimPEG')

M = S.TensorMesh(np.ones(10))

print S.vectorCCx(M)Summary¶

I have started to translate some of the SimPEG functionality of the Mesh class over to Julia, and it was a pretty easy translation. It is certainly nice to have some of the ease of notation back when dealing with vectors and matrices, some of this is cumbersome in Python/scipy. The lack of OOP in Julia makes sense from a numerical computing side of things, but when you are building a bigger package/project (like SimPEG) these things are crucial to have. Representing some of the higher level concepts (e.g. DataMisfit, Regularization) doesn’t really make sense as a Type, because the primary things in those classes are methods rather than variables. There seems to be some level of interoperability between the languages, but it is much better in the Julia calling Python direction; this will likely improve in the future. I am excited about the combination of these languages, and exploring some of the parallel features of Julia in the coming months.

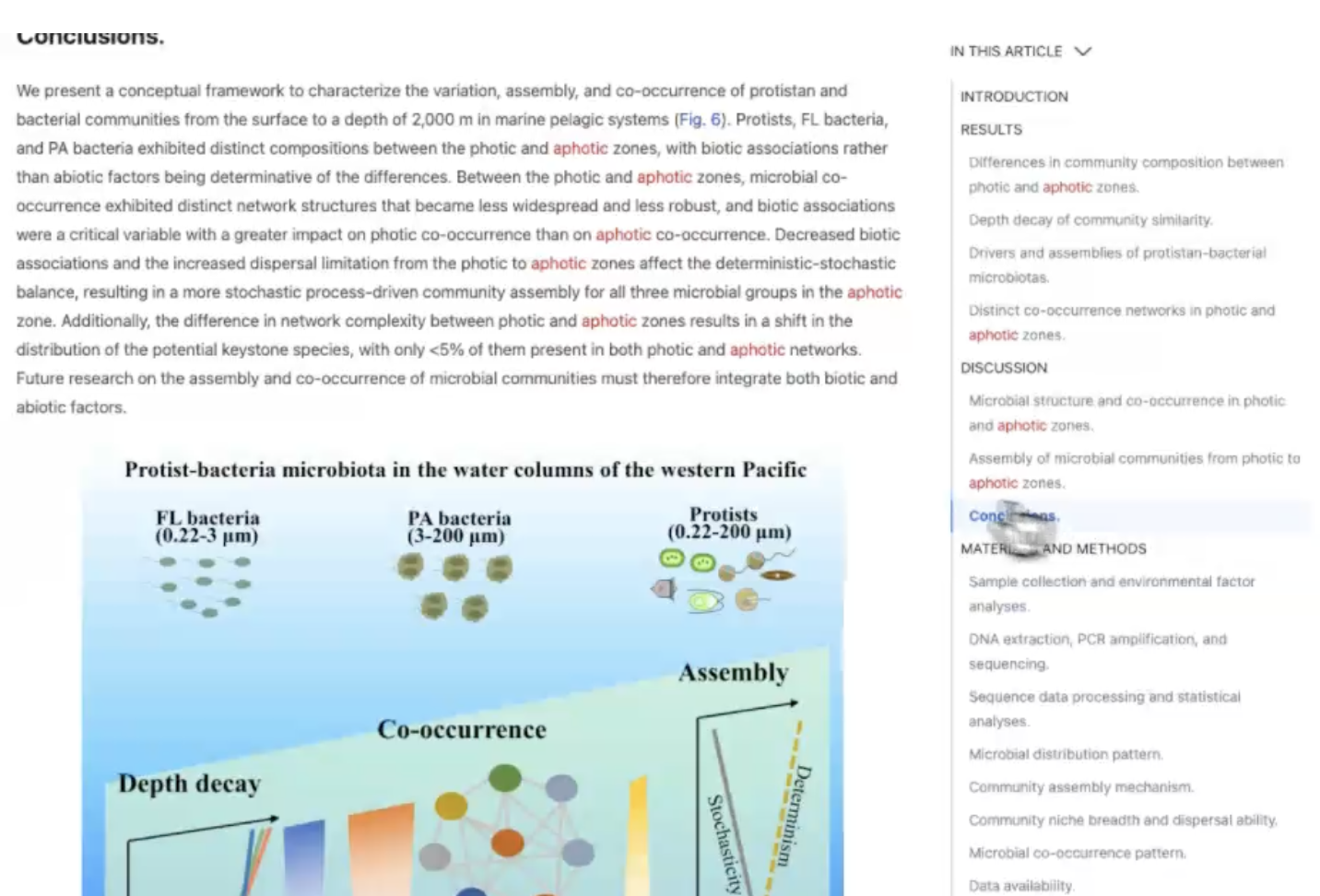

What if scientific articles were a bit more like IDEs and you could highlight a word and see where those abbreviations or words are used throughout the document.

Reflecting on creating tools for technical communication.

Seismic velocity in layers.

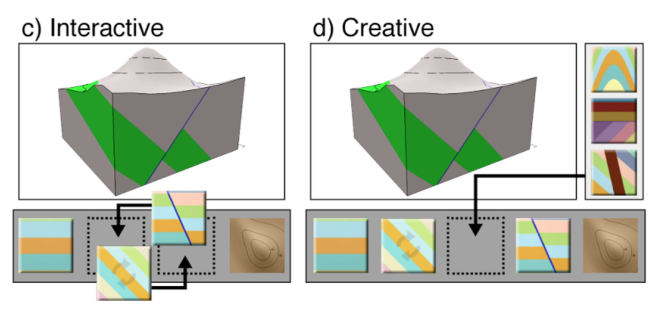

My motivations behind developing components.ink and a comparison to Tangle and Idyll Lang

UCalgary Geosicence - Friday Afternoon Talk Series