On Research

I was solving one problem after another after another; a fair number were successful and there were a few failures. I went home one Friday after finishing a problem, and curiously enough I wasn’t happy; I was depressed. I could see life being a long sequence of one problem after another after another. After quite a while of thinking I decided, “No, I should be in the mass production of a variable product. I should be concerned with all of next year’s problems, not just the one in front of my face.” By changing the question I still got the same kind of results or better, but I changed things and did important work. I attacked the major problem.

You and Your Research (Richard Hamming, 1986)

A story¶

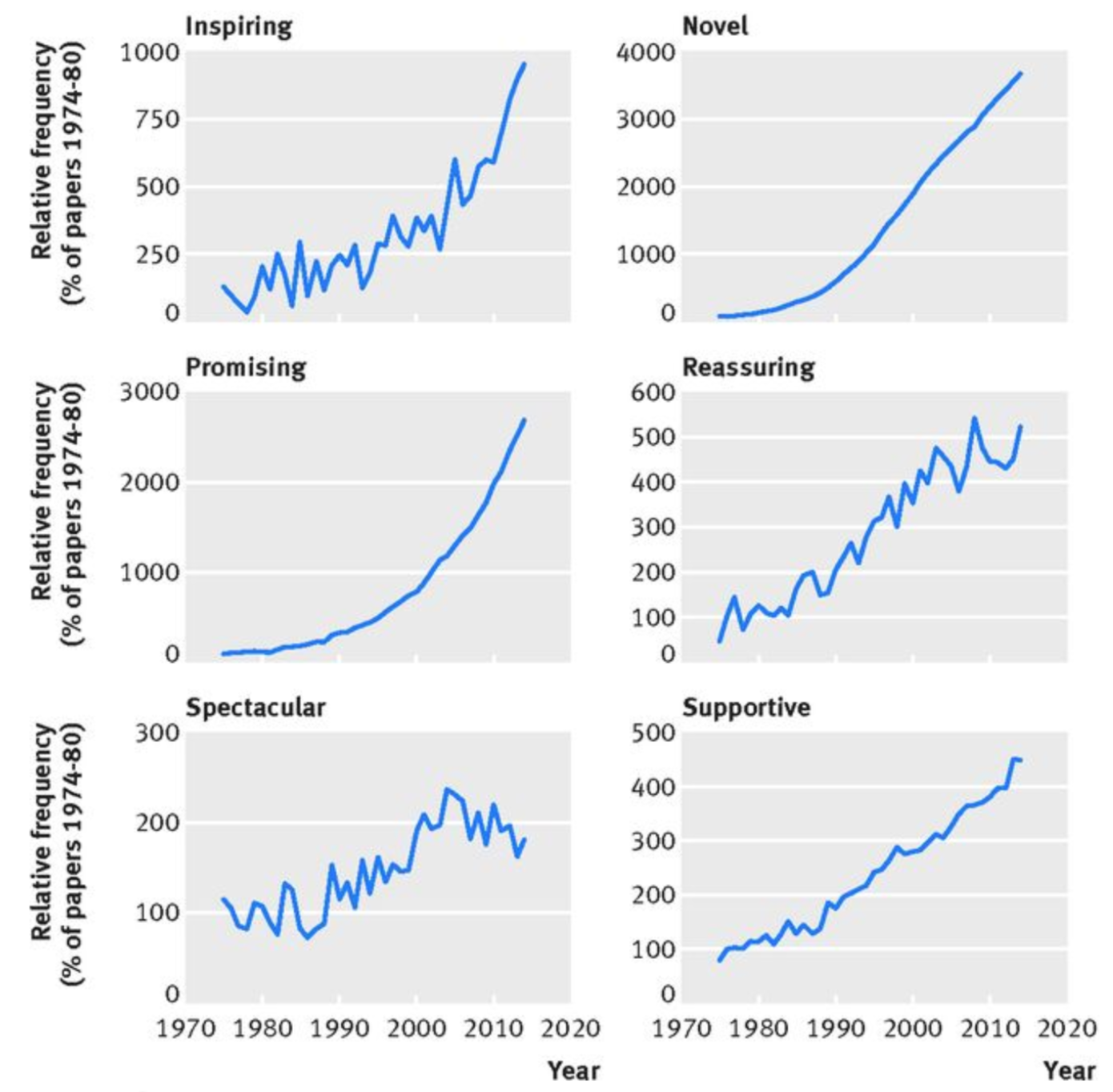

Throughout my PhD I have heard a story around what research is. You must take a single idea in a field, dive into the details, and show how that idea is wrong, or can be drastically improved by your tweak. Research must be novel, groundbreaking, amazing, innovative, robust, and unprecedented. Unprecedented means never known or done before. Ever. Really? Not even one giant involved? The scientific literature is plagued by the nonsense of differentiation. You must say how you stand apart from the herd. Your work is the special one. But. If you stand apart, and are always focused on the differences, you will miss the similarities. You will hinder the real progress being made by a community of people all doing the exact same thing: contributing to the advancement of the entire field. Splintered ideas throughout multiple journals, which focus almost entirely on their own uniqueness, are not contributions. These papers, of course, have a nod to the (now irrelevant) work that has come before in a “literature review” but they really only cite (a) fundamental work done in the 60s, (b) their own work, and (c) the work of the reviewers who you had to please along the way.

I have been told this story, and have been encouraged to attack a number of the small problems in the field of geophysics. There are, however, some big problems in our field and part of my research has been to identify and attack those, rather than to cultivate a series of splintered ideas. These are instances of a larger class of problem. It has taken much energy and imagination to say no to that path: in the end, I suppose, it is my PhD.

In physics¶

In physics the goal that we are taught, the ideal towards which to strive, is a universal set of equations. Bring all of those pesky fields of electricity, magnetism, gravity, and forces strong and weak together: in a single framework. Why? Why bother? Why not expand each field of physics by iterating on our tiny details, by inventing new equations that explain the physics in our case study, by nodding to other fields in a literature review but carrying on uninhibited. The goal of physics is not to have a large mess of disconnected equations and explanations, but to have a simple, elegant explanation of how things work. If you take each methodology to the limit you will have either a mess of disconnected ideas or an elegant explanation that informs many fields. The goal is something small. Concise. Simple. The goal is to generalize but not to sacrifice any data points. The goal, I believe, is a framework. A framework is a lattice work on which ideas can be placed; a map to give you direction and orientation of where your ideas fit in; it is actionable, extensible and rigorously tested against reality; it can be communicated succinctly; and it is a way to illuminate the path to future work.

In geophysics¶

In applied geophysics, I believe that we are also plagued by the general trend to isolate our ideas and brag about our novel work. We also have a significant amount of effort ahead of us if we would like to communicate and collaborate with our geoscience peers in geology, geochemistry, and hydrogeology. This communication and integration is the webbing on which the future of our field depends, and it is not aided by the focus on differentiation. To contribute to the field of geophysics, I have chosen to work on a framework, on the webbing between disciplines. My starting place has been focused on geophysics that uses simulation and parameter estimation. There is a lot going on in this field, and I have tried to summarize and/or reproduce a large quantity of the literature. This has been difficult due to the way in which these ideas have been left: vague recipes that have the majority of the numerical instructions missing, often intentionally to maintain the researchers competitive advantage. This proprietary paradigm does not appeal to my scientific morals, and as such, I have also tried to complete all of my research such that it is open and reproducible. I have looked to other fields on how to organize a community around open, accessible, usable ideas. Much of the following work is “implementation” and “engineering” in its nature. However, this is not the idea I have sought to cultivate, it is the way in which I test, extend, and generalize that idea in a rigorous, scientific way. The idea which I have nurtured is a framework for simulation and parameter estimation in geophysics, it is a work in progress, it is a community effort, and, I believe, it is research. It is wrong but useful, as all models are, and it is a start, with a few good ideas.

Context¶

I wrote this article when struggling with how to focus my PhD dissertation. Many rather senior professors I talked with casually dismissed much of my PhD with sweeping comments of “That’s not research”. This annoyed me enough into changing the focus of my PhD to this non-research almost entirely (much to the dismay of some of my committee, ha - I graduated, so I can laugh!). I felt like it was important work to rigorously study, research - you might say, how various geoscience fields fit together. Without this type of research, there would be a crushing debt of all sorts of geophysical methods that don’t work together.

I followed this article up with a slightly less caustic version On Breakthroughs, that tried to illustrate a more diverse view on research that highlights both the creation as well as the curation of ideas.

Rather than propose a new theory or unearth a new fact, often the most important contribution a scientist can make is to discover a new way of seeing old theories or facts.

The Selfish Gene (Richard Dawkins, 1989)

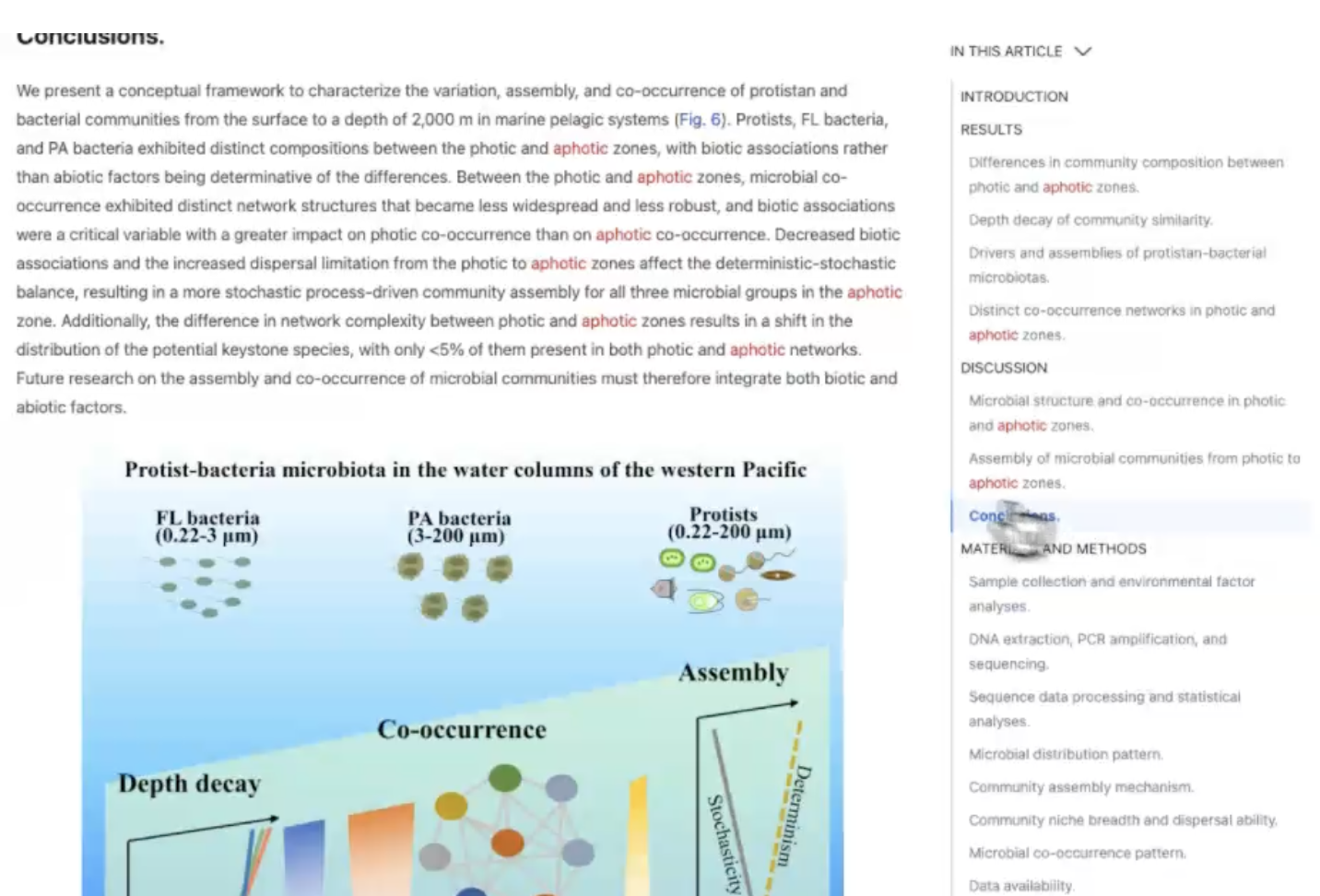

What if scientific articles were a bit more like IDEs and you could highlight a word and see where those abbreviations or words are used throughout the document.

Reflecting on creating tools for technical communication.

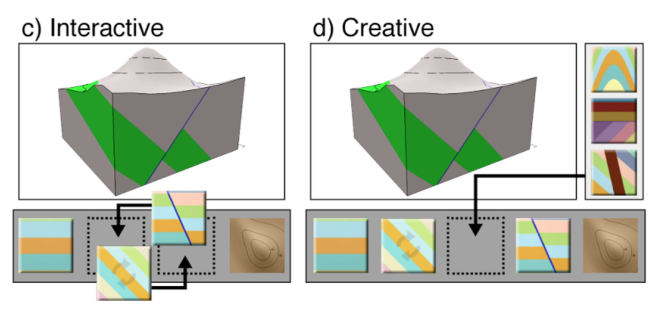

Seismic velocity in layers.

My motivations behind developing components.ink and a comparison to Tangle and Idyll Lang

Podcast with Matt Hall and Graham Ganssle